TL;DR: The S force should have a potential of the form ![]() , where

, where ![]() is a modified Bessel function of the second kind, not

is a modified Bessel function of the second kind, not ![]() as I previously thought. I will be correcting the existing posts to account for this eventually, but it will take a while.

as I previously thought. I will be correcting the existing posts to account for this eventually, but it will take a while.

Massive Bosons

In order to avoid electrons falling all the way into nuclei and to make chemistry in 4D work at all, I found it necessary to introduce a short-range repulsive force between the nuclei and electrons (which I call “the S force”). Thankfully physics provides a reasonable way for short-range forces to work. Every force in particle physics has a boson associated with it, and if the boson has a non-zero mass, the force has a limited range.

The electromagnetic force is associated with photons, and it obeys Maxwell’s Equations. The usual form of these equations is in terms of the electric and magnetic fields ![]() and

and ![]() , but if we express these both in terms of the electric potential

, but if we express these both in terms of the electric potential ![]() and magnetic potential

and magnetic potential ![]() as

as

(1)

then combine these into the spacetime vector potential1usually called “four-vector” rather than “spacetime vector”, but with 4 spatial dimensions, spacetime vectors are five-vectors instead, so this terminology generalizes better ![]() with

with ![]() , and likewise combine the current and charge density into a spacetime vector

, and likewise combine the current and charge density into a spacetime vector ![]() , then the equations become

, then the equations become

(2)

This is the equation for a massless particle like the photon. For a massive particle, an extra term in the equation is needed.2To see that this indeed corresponds to a particle of mass ![]() , take the plane-wave solutions and use the quantum energy and momentum relations

, take the plane-wave solutions and use the quantum energy and momentum relations ![]() and

and ![]() , then this gives the correct relativistic energy relation for a single particle.

, then this gives the correct relativistic energy relation for a single particle.

(3) ![]()

In the case of a static charge configuration, this simplifies to

(4)

Potentials

The wave equations themselves were unchanged between 3D and 4D, but when we consider their solutions, they start to differ. Without the mass term, and with a single point charge ![]() , the general solution for

, the general solution for ![]() is

is

(5)

where ![]() is the surface area of a unit sphere in

is the surface area of a unit sphere in ![]() -dimensional space. This becomes

-dimensional space. This becomes ![]() in 3D and

in 3D and ![]() in 4D3I previously had

in 4D3I previously had ![]() for 4D, a second error which thankfully does not actually affect anything as I immediately got rid of the

for 4D, a second error which thankfully does not actually affect anything as I immediately got rid of the ![]() factor anyway. Although the potential decreases asymptotically to

factor anyway. Although the potential decreases asymptotically to ![]() as

as ![]() tends to infinity, it decreases rather slowly. If there is a roughly uniform charge density over a wide area, then the potential at any point in that area is dominated by the distant charges rather than the nearby ones, because the potential from a distance

tends to infinity, it decreases rather slowly. If there is a roughly uniform charge density over a wide area, then the potential at any point in that area is dominated by the distant charges rather than the nearby ones, because the potential from a distance ![]() decreases like

decreases like ![]() while the volume (and thus charge) at that distance increases as

while the volume (and thus charge) at that distance increases as ![]() . Things like this are the reason the electromagnetic force is described as long-range. Gravity, although it follows different fundamental equations, has the same

. Things like this are the reason the electromagnetic force is described as long-range. Gravity, although it follows different fundamental equations, has the same ![]() potential in 3D in ordinary cases, which is why it’s long-range too.

potential in 3D in ordinary cases, which is why it’s long-range too.

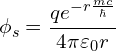

Now let’s consider the case of non-zero mass. In 3D, the potential from a point charge is

(6)

This is called “the Yukawa potential”. It decreases exponentially with distance, so at distances much greater than ![]() , it quickly becomes negligible. The range of the force is inversely proportional to the boson’s mass, and if the mass is set to

, it quickly becomes negligible. The range of the force is inversely proportional to the boson’s mass, and if the mass is set to ![]() , it becomes the usual Coulomb potential, with infinite range.

, it becomes the usual Coulomb potential, with infinite range.

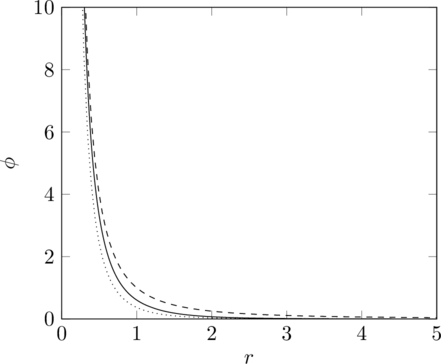

Here is a plot of the 3D Coulumb and Yukawa potentials (with ![]() ) to illustrate the rapid decrease.

) to illustrate the rapid decrease.

When I started this 4D chemistry project, I just assumed that the formula for the Yukawa potential generalized to 4D in the obvious way, as ![]() for some

for some ![]() and

and ![]() . It turns out however, that this is not actually a solution to Equation 4, and the real solution in 4D is much more complicated.

. It turns out however, that this is not actually a solution to Equation 4, and the real solution in 4D is much more complicated.

(7)

The function ![]() here is the modified Bessel function of the second kind (with parameter 1). It is a function that can’t be expressed in closed form in terms of more standard functions like exponentials and trig functions, but just like the exponential function is defined as a solution to the differential equation

here is the modified Bessel function of the second kind (with parameter 1). It is a function that can’t be expressed in closed form in terms of more standard functions like exponentials and trig functions, but just like the exponential function is defined as a solution to the differential equation ![]() , and sin and cos are defined as solutions to

, and sin and cos are defined as solutions to ![]() ,

, ![]() is defined by

is defined by ![]() . Like with sin and cos, there are 2 linearly independent solutions, the modified Bessel functions of the first and second kind,

. Like with sin and cos, there are 2 linearly independent solutions, the modified Bessel functions of the first and second kind, ![]() and

and ![]() (

(![]() corresponds to another solution to Equation 4, with the charge at infinity in all directions instead of at the origin).

corresponds to another solution to Equation 4, with the charge at infinity in all directions instead of at the origin).

![]() is approximately

is approximately ![]() for

for ![]() near

near ![]() , so the Yukawa potential, as expected, again matches the Coulomb potential for

, so the Yukawa potential, as expected, again matches the Coulomb potential for ![]() , or for

, or for ![]() . For

. For ![]() ,

, ![]() , therefore

, therefore ![]() .

.

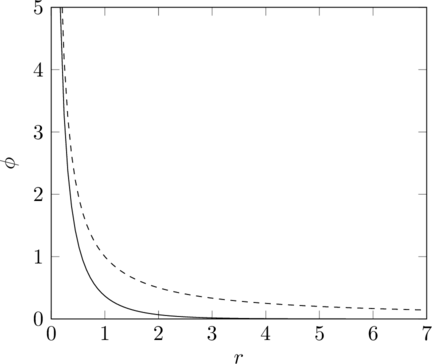

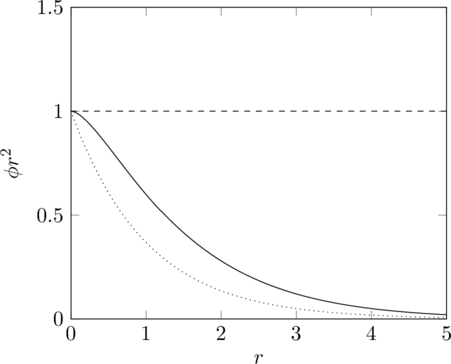

Here the Coulomb potential is shown as the dashed line, the Yukawa potential for ![]() is the solid line, and the incorrect Yukawa potential I have been using previously is the dotted line. The

is the solid line, and the incorrect Yukawa potential I have been using previously is the dotted line. The ![]() dependence dominates all three plots, making the other details harder to distinguish, so here is a plot with that factor removed.

dependence dominates all three plots, making the other details harder to distinguish, so here is a plot with that factor removed.

Corrections

As my simulations and previous posts have been based on the incorrect version of the Yukawa potential, they will need to be fixed. I’m not sure whether it’s worth leaving the old versions or not. It would seem a shame to just delete the previous version if there are substantial changes, but also I don’t really want the incorrect version to be what people see when they read the blog.

The new version is more complicated than the old one, and it will probably take some work to implement efficient approximations to ![]() (as unlike the exponential function, programming languages don’t generally have it built in (I already had to use an approximation just to make the graphs above)), then a lot more work to re-run the simulations and re-adjust the parameters. As you can see from the graph, with the same parameters the correct version of the Yukawa potential is greater than the old version, so the overall strength of the S force will probably need to be decreased somewhat to compensate.

(as unlike the exponential function, programming languages don’t generally have it built in (I already had to use an approximation just to make the graphs above)), then a lot more work to re-run the simulations and re-adjust the parameters. As you can see from the graph, with the same parameters the correct version of the Yukawa potential is greater than the old version, so the overall strength of the S force will probably need to be decreased somewhat to compensate.

Until I run the simulations, I don’t really have much idea of what the changes will be. Most of the changes will be minor, as the exact shape of the potential near the nucleus is not generally all that important. As that region is repulsive, the electrons are already unlikely to be there. The corrected version of the potential is somewhat less sharp than the old one, so maybe the electrons will penetrate into the centre a little more. All the general results about scaling and spin and so on remain unaffected, because they don’t depend on the particular form of the S force in the first place. I have even previously considered using a hard-core potential (i.e. the electrons would be completely unable to approach within a certain radius of the nuclei, and not repelled at all outside that radius) instead of a Yukawa potential because it’s the other simplest option.

The corrections will probably take a while, and until they’re done I probably won’t be publishing many new posts, but hey, it’s not like I was publishing new posts that often in the first place.

An Aside on S Boson Spin

The original force the Yukawa potential was invented to describe was the nuclear force, a.k.a. the residual strong force. This is associated with pions, a massive boson which, unlike photons, have spin 0, so their field is a scalar rather than vector. This raises the question of whether to also make S bosons scalars. The main difference is that with scalar bosons, like charges attract. The main criterion for the S force is that electrons and nuclei are repelled from each other, and they could just have opposite charges to make this fit, but then nuclei would still be attracted to each other, making nuclear fusion far too easy. Perhaps it would be possible to tune the parameters so that the electrostatic repulsion is greater than the S attraction, but that puts annoying constraints on the parameters that conflict with what I want for chemistry, which is after all the actual point of this project. I will therefore be sticking with S bosons being spin 1, vectors.

- 1usually called “four-vector” rather than “spacetime vector”, but with 4 spatial dimensions, spacetime vectors are five-vectors instead, so this terminology generalizes better

- 2To see that this indeed corresponds to a particle of mass

, take the plane-wave solutions and use the quantum energy and momentum relations

, take the plane-wave solutions and use the quantum energy and momentum relations  and

and  , then this gives the correct relativistic energy relation for a single particle.

, then this gives the correct relativistic energy relation for a single particle. - 3I previously had

for 4D, a second error which thankfully does not actually affect anything as I immediately got rid of the

for 4D, a second error which thankfully does not actually affect anything as I immediately got rid of the  factor anyway

factor anyway

Leave a Reply