Counting Orbitals: The Brief Version

Although technically all of the electrons in an atom (and indeed the whole world) share a single many-dimensional wavefunction, most of the time it is possible to approximate each electron in an atom or molecule as having a separate wavefunction. These are functions ![]() from positions to probability amplitudes, so that the value

from positions to probability amplitudes, so that the value ![]() at a particular spatial position

at a particular spatial position ![]() relates to the probability that the electron is at that location (the probability density is

relates to the probability that the electron is at that location (the probability density is ![]() ). A valid one-electron wavefunction is also called an “orbital”, because they are the quantum analogue of orbits in classical physics. Each orbital has a specific energy associated with it, and at most two electrons can occupy each orbital (the Pauli exclusion principle), so (with some corrections for the mutual repulsion between the electrons) if there are

). A valid one-electron wavefunction is also called an “orbital”, because they are the quantum analogue of orbits in classical physics. Each orbital has a specific energy associated with it, and at most two electrons can occupy each orbital (the Pauli exclusion principle), so (with some corrections for the mutual repulsion between the electrons) if there are ![]() electrons in the atom, they will usually be found occupying the

electrons in the atom, they will usually be found occupying the ![]() lowest energy orbitals of the atom.

lowest energy orbitals of the atom.

The electric field of the nucleus (and in 4D its S field too), which is the main contributor to the energy of the orbitals, is spherically symmetrical, therefore if two orbitals have the same shape but in different orientations, they have the same energy. This leads to sets of orbitals, called “sub-shells”, where all the orbitals in each sub-shell have the same energy.

Not every possible rotation necessarily leads to a distinct orbital for the purposes of the exclusion principle, even if the orbital is not at all symmetrical. If ![]() and

and ![]() are orbitals, then any linear combination of them, does not count as a separate orbital. For example, if there is an orbital

are orbitals, then any linear combination of them, does not count as a separate orbital. For example, if there is an orbital ![]() , this can be rotated by 90° to give

, this can be rotated by 90° to give ![]() , but rotating it 45° gives

, but rotating it 45° gives ![]() , which is a linear combination of the previous two functions. Rotating this orbital can only give 3 linearly independent orbitals (in 3D), one each for x y and z.

, which is a linear combination of the previous two functions. Rotating this orbital can only give 3 linearly independent orbitals (in 3D), one each for x y and z.

In this way, the sub-shells come in certain characteristic sizes, which depend on the dimension. Spherical orbitals, called “s”, only have one orbital per sub-shell because they’re already symmetrical. P orbitals are positive on one side and negative on the other, and there is one aligned with each axis, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and in 4D, also

, and in 4D, also ![]() . D orbitals have a greater variety of shapes but most of them are split in four parts, with the sign alternating between quadrants. In 3D, there are 5 of them,

. D orbitals have a greater variety of shapes but most of them are split in four parts, with the sign alternating between quadrants. In 3D, there are 5 of them, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , and in 4D there are 4 extra,

, and in 4D there are 4 extra, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . The formula, which I’ll derive later, is in general

. The formula, which I’ll derive later, is in general ![]() in 3D, and

in 3D, and ![]() in 4D (where

in 4D (where ![]() is s,

is s, ![]() is p,

is p, ![]() is d, etc.).

is d, etc.).

The sizes of the sub-shells are part of what gives the periodic table its particular shape. For each period, there are two elements whose highest-energy filled orbital is an s orbital (the alkaline and alkali earth metals, or exceptionally in period 1, hydrogen and helium), 6 with it being the p orbitals (starting from period 2, the mostly non-metals at the right of the table), 10 with d (starting from period 4, the transition metals), and 14 with f (starting from period 6, the lanthanides and actinides). You might therefore expect that in 4D, there are 8 p-block elements per period, 18 d-block elements, 50 f-block elements, and so on, but it turns out this is not exactly true, because the orderly periodic structure instead breaks down entirely.

Separating Solutions

Because of the linearity and spherical symmetry of the Schrödinger equation for a single electron in a single atom, given any orbital ![]() , it is possible to combine rotated copies of

, it is possible to combine rotated copies of ![]() to obtain an orbital which can be expressed as the product of a radial part

to obtain an orbital which can be expressed as the product of a radial part ![]() which depends only on the distance between the electron and the nucleus, and an angular part

which depends only on the distance between the electron and the nucleus, and an angular part ![]() which depends only on the direction of the position vector

which depends only on the direction of the position vector ![]() but not its length. A general orbital can be expressed as a sum of these separable orbitals, and the separated form is often easier to work with, and in many cases any orbital with definite energy is separable already, so these are the form that are usually used. Orbitals labelled s, p, d, etc. are in this separable form.

but not its length. A general orbital can be expressed as a sum of these separable orbitals, and the separated form is often easier to work with, and in many cases any orbital with definite energy is separable already, so these are the form that are usually used. Orbitals labelled s, p, d, etc. are in this separable form.

Because ![]() describes the variation in

describes the variation in ![]() in the tangiential direction, and the momentum is related to the derivative of the wavefunction,

in the tangiential direction, and the momentum is related to the derivative of the wavefunction, ![]() is related to the momentum perpendicular to the nucleus, and thus to the angular momentum. It will turn out that

is related to the momentum perpendicular to the nucleus, and thus to the angular momentum. It will turn out that ![]() describes the electron’s angular momentum completely, apart from the spin angular momentum, which is why this page entitled “Angular Momentum” is really about this separation of variables and the implications of its angular part.

describes the electron’s angular momentum completely, apart from the spin angular momentum, which is why this page entitled “Angular Momentum” is really about this separation of variables and the implications of its angular part.

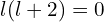

Let’s substitute a separated wavefunction into the time-independent Schrödinger equation. Here ![]() and

and ![]() are functions of

are functions of ![]() , and

, and ![]() is a function of

is a function of ![]() .

.

In this last equation, every term is proportional (at a constant radius) to ![]() except for one which is proportional to

except for one which is proportional to ![]() , therefore unless

, therefore unless ![]() is everywhere

is everywhere ![]() (which is impossible), there must be some constant of proportionality

(which is impossible), there must be some constant of proportionality ![]() such that

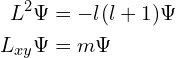

such that ![]() (the usual notation is

(the usual notation is ![]() instead of

instead of ![]() , because

, because ![]() is the eigenvalue of the angular momentum squared operator

is the eigenvalue of the angular momentum squared operator ![]() applied to the whole orbital, but in this particular equation it doesn’t make sense to use the operator instead of the eigenvalue). Substituting this back in gives the equation for

applied to the whole orbital, but in this particular equation it doesn’t make sense to use the operator instead of the eigenvalue). Substituting this back in gives the equation for ![]() ,

,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[E\Psi = -\frac 1 2 \Psi'' - \frac {d-1} {2r} \Psi' + \left(V - \frac {E_l} {2 r^2}\right) \Psi.\]](https://blog.4denthusiast.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-3bd1e0f7450250fe3e244ed47af86a3b_l3.png)

There are more implications of this radial equation to discuss, but for now let’s focus on the angular part, ![]() . This is the equation for spherical harmonics, so the question becomes what spherical harmonics are there in 3D and 4D, and what are the corresponding values of

. This is the equation for spherical harmonics, so the question becomes what spherical harmonics are there in 3D and 4D, and what are the corresponding values of ![]() ?

?

Let ![]() , where

, where ![]() , then

, then ![]() . There are no spherical harmonics with

. There are no spherical harmonics with ![]() positive, therefore there is always a suitable

positive, therefore there is always a suitable ![]() .

. ![]() is a solution to Laplace’s equation, therefore it is analytic and there is some polynomial

is a solution to Laplace’s equation, therefore it is analytic and there is some polynomial ![]() such that

such that ![]() for

for ![]() sufficiently small, therefore as

sufficiently small, therefore as ![]() ,

, ![]() too (i.e. it’s homogeneous), therefore

too (i.e. it’s homogeneous), therefore ![]() everywhere, and in particular, for unit vectors

everywhere, and in particular, for unit vectors ![]() ,

, ![]() . There is therefore a correspondence between spherical harmonics of eigenvalue

. There is therefore a correspondence between spherical harmonics of eigenvalue ![]() and homogeneous polynomials of degree

and homogeneous polynomials of degree ![]() with zero Laplacian, and it goes the other way too, so to count the spherical harmonics, we just need to count the polynomials.

with zero Laplacian, and it goes the other way too, so to count the spherical harmonics, we just need to count the polynomials.

The homogeneous polynomials of degree ![]() , those which satisfy

, those which satisfy ![]() , can alternatively be characterized as those polynomials made up of monomials

, can alternatively be characterized as those polynomials made up of monomials ![]() where

where ![]() . With

. With ![]() variables, the number of monomials is just the number of ways to partition

variables, the number of monomials is just the number of ways to partition ![]() equivalent objects into

equivalent objects into ![]() groups, which is the binomial coefficient

groups, which is the binomial coefficient ![]() . The set of homogeneous polynomials of degree

. The set of homogeneous polynomials of degree ![]() in

in ![]() variables forms a vector space of dimension

variables forms a vector space of dimension ![]() because the monomials are a basis, and it is the dimension of the space that determines the number of orbitals. There is also the restriction on the Laplacian to consider. The Laplacian of a homogeneous degree

because the monomials are a basis, and it is the dimension of the space that determines the number of orbitals. There is also the restriction on the Laplacian to consider. The Laplacian of a homogeneous degree ![]() polynomial is a homogeneous degree

polynomial is a homogeneous degree ![]() polynomial, and these form a

polynomial, and these form a ![]() dimensional space. The Laplacian is a linear map between these vector spaces, and it’s surjective, therefore by the Rank-Nullity Theorem the subspace consisting of polynomials with zero Laplacian has dimension

dimensional space. The Laplacian is a linear map between these vector spaces, and it’s surjective, therefore by the Rank-Nullity Theorem the subspace consisting of polynomials with zero Laplacian has dimension ![]() , which simplifies (for

, which simplifies (for ![]() ) to

) to ![]() , or

, or ![]() for 3D and

for 3D and ![]() in 4D. Since it is the value of

in 4D. Since it is the value of ![]() that influences the energy of the orbital, these numbers of spherical harmonics for each

that influences the energy of the orbital, these numbers of spherical harmonics for each ![]() directly determine the number of orbitals in each sub-shell.

directly determine the number of orbitals in each sub-shell.

Although it’s not relevant to the 4D chemistry, here are the sub-shell sizes the general formula gives for some other dimensions. These are just the numbers of orbitals, the number of electrons per orbital (i.e. the number of spin states) also varies by dimension, although it’s the same in 3D and 4D.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Label | s | p | d | f | |

| 1D | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2D | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3D | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | |

| 4D | 1 | 4 | 9 | 16 | |

| 5D | 1 | 5 | 14 | 30 | |

| 6D | 1 | 6 | 20 | 50 | |

| 1 |

The polynomials, which determine the particular shape and orientation of each orbital within a subshell, are the source of the labels, ![]() etc.. The particular set of polynomials chosen for each value of

etc.. The particular set of polynomials chosen for each value of ![]() is somewhat arbitrary, they just need to be an orthogonal basis for the space of degree

is somewhat arbitrary, they just need to be an orthogonal basis for the space of degree ![]() homogeneous polynomials in

homogeneous polynomials in ![]() variables with zero Laplacian.

variables with zero Laplacian.

Orbital Ordering

The angular momentum quantum number ![]() characterizes the angular part of the orbital, as we’ve seen. The radial part, being a function from positive real numbers to reals1in principle it takes complex values, but all of the actual solutions can be made real just by a re-scaling, in general oscillates some number of times between positive and negative, and decays asymptotically to 0 at infinity. (If it does not decay at infinity it does not represent a state where the electron is actually attached to the atom.) There is at most a single solution for each number of oscillations, so let’s use the number of distinct regions of a single sign as a second quantum number

characterizes the angular part of the orbital, as we’ve seen. The radial part, being a function from positive real numbers to reals1in principle it takes complex values, but all of the actual solutions can be made real just by a re-scaling, in general oscillates some number of times between positive and negative, and decays asymptotically to 0 at infinity. (If it does not decay at infinity it does not represent a state where the electron is actually attached to the atom.) There is at most a single solution for each number of oscillations, so let’s use the number of distinct regions of a single sign as a second quantum number ![]() to characterize the radial wavefunction.

to characterize the radial wavefunction. ![]() can equivalently be defined as 1 + the number of zeroes of the radial wavefunction, not counting the zero at

can equivalently be defined as 1 + the number of zeroes of the radial wavefunction, not counting the zero at ![]() that may occur in 4D.

that may occur in 4D.

In 3D, in the absence of other electrons, orbitals with the same value of ![]() have the same energy. The mathematical reasons for this are rather complicated, but I think it relates to the fact that classical mechanics in 3D gives periodic elliptical orbits. I generally just think of this fact as essentially a coincidence, and it’s a coincidence that does not carry over to 4D.

have the same energy. The mathematical reasons for this are rather complicated, but I think it relates to the fact that classical mechanics in 3D gives periodic elliptical orbits. I generally just think of this fact as essentially a coincidence, and it’s a coincidence that does not carry over to 4D.

Because of this coincidence, the actual quantum number usually used in 3D instead of ![]() is the principal quantum number

is the principal quantum number ![]() . Just as the sets of orbitals with the same

. Just as the sets of orbitals with the same ![]() and

and ![]() are called “sub-shells”, the sets of orbitals with equal

are called “sub-shells”, the sets of orbitals with equal ![]() but possibly differing

but possibly differing ![]() are called “shells”. In actual atoms with multiple electrons, the sub-shells in each shell have somewhat different energies, because the repulsion between the electrons modifies the shape of the effective potential.

are called “shells”. In actual atoms with multiple electrons, the sub-shells in each shell have somewhat different energies, because the repulsion between the electrons modifies the shape of the effective potential.

Another important factor in 3D chemistry is that the orbitals of a single electron around any nucleus are the same shape and energy as the orbitals in a hydrogen atom, except that the size is scaled by ![]() , and the energies by

, and the energies by ![]() . (This relates to the fact, discussed in the Parameters post, that in 3D chemistry there are no parameters that actually matter, at least at this level of approximation.) This means that the ordering of the energies of the orbitals does not change with atomic number. Again, the repulsion between the electrons makes this not exactly true for complete atoms, but the fact that it remains somewhat true is a major factor in why the periodic table has the orderly shape it does. In most cases, as you go from one element to the next, the

. (This relates to the fact, discussed in the Parameters post, that in 3D chemistry there are no parameters that actually matter, at least at this level of approximation.) This means that the ordering of the energies of the orbitals does not change with atomic number. Again, the repulsion between the electrons makes this not exactly true for complete atoms, but the fact that it remains somewhat true is a major factor in why the periodic table has the orderly shape it does. In most cases, as you go from one element to the next, the ![]() atom has the same electron arrangement as the

atom has the same electron arrangement as the ![]() ion, then the neutral

ion, then the neutral ![]() atom just has its extra electron in whatever subshell was already part filled, or the next subshell up if the previous one is full. There are minor exceptions, but they don’t change the overall periodic structure much. In 4D, this is not at all the case.

atom just has its extra electron in whatever subshell was already part filled, or the next subshell up if the previous one is full. There are minor exceptions, but they don’t change the overall periodic structure much. In 4D, this is not at all the case.

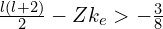

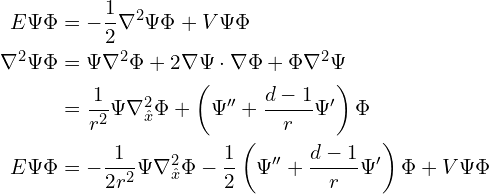

Let’s substitute the potential for a 4D atom into the radial part of the Schrödinger equation.

Because the centrifugal term ![]() has the same dependence on

has the same dependence on ![]() as the Coulumb term

as the Coulumb term ![]() does (unlike in 3D where the Coulumb term is proportional to

does (unlike in 3D where the Coulumb term is proportional to ![]() ), the effect of the angular momentum on the radial part of the Schrödinger equation, and therefore on the energy of the orbital, is the same as a decrease in nuclear charge. This has several consequences:

), the effect of the angular momentum on the radial part of the Schrödinger equation, and therefore on the energy of the orbital, is the same as a decrease in nuclear charge. This has several consequences:

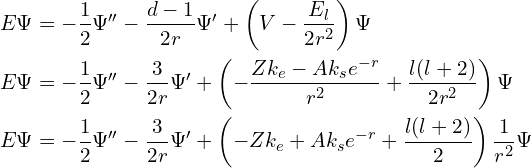

- The coincidence of equal

but different

but different  orbitals having the same energy does not hold in 4D. The principal quantum number

orbitals having the same energy does not hold in 4D. The principal quantum number  , as defined in 3D, therefore isn’t of much use, and it makes more sense to just use

, as defined in 3D, therefore isn’t of much use, and it makes more sense to just use  . Let’s call it the radial quantum number. For

. Let’s call it the radial quantum number. For  much higher than

much higher than  , orbitals with the same value of

, orbitals with the same value of  have approximately the same energy, so perhaps we could call these shells instead, but they aren’t very relevant for the outer electrons which are most involved in chemical bonding, so this modified concept of shells probably isn’t very useful. I’m not sure whether naming orbitals by

have approximately the same energy, so perhaps we could call these shells instead, but they aren’t very relevant for the outer electrons which are most involved in chemical bonding, so this modified concept of shells probably isn’t very useful. I’m not sure whether naming orbitals by  (so 2p has

(so 2p has  ) or

) or  (so 2p has

(so 2p has  ) is less confusing, but for this post at least I’ll be going with

) is less confusing, but for this post at least I’ll be going with  .

. - If

,2I’m not quite sure yet this is the right criterion. I realised there was an error in my original reasoning only after publishing the post, and I’ve not yet worked out the correct answer, but this should be approximately right) the effective potential is not attractive enough for electron to be bound. With my usual value of

,2I’m not quite sure yet this is the right criterion. I realised there was an error in my original reasoning only after publishing the post, and I’ve not yet worked out the correct answer, but this should be approximately right) the effective potential is not attractive enough for electron to be bound. With my usual value of  , s orbitals with

, s orbitals with  are always bound, p orbitals are bound for

are always bound, p orbitals are bound for  , d orbitals are bound for

, d orbitals are bound for  , and f orbitals are bound for

, and f orbitals are bound for  .

.

- Hydrogen’s only excited states are 2s, 3s, 4s, etc.. No

states are bound. Because s to s transitions are all forbidden, hydrogen does not have an atomic spectrum. Its excited states can still decay very slowly via two-photon emission (hydrogen’s 2s excited state in 3D has a lifetime of about half a second, which is exceptionally long for this sort of thing), but two photon emissions don’t produce spectral lines. Helium is similar, and lithium does have some excited states, but probably only with its 1s shell at least partially empty.

states are bound. Because s to s transitions are all forbidden, hydrogen does not have an atomic spectrum. Its excited states can still decay very slowly via two-photon emission (hydrogen’s 2s excited state in 3D has a lifetime of about half a second, which is exceptionally long for this sort of thing), but two photon emissions don’t produce spectral lines. Helium is similar, and lithium does have some excited states, but probably only with its 1s shell at least partially empty. - For the next few elements after a noble gas (to the extent there are noble gases without shells), the effective nuclear charge for the valence electrons, taking into account the repulsion from the other electrons, is approximately the number of valence electrons (or somewhat less because they’re also repelled from each other, not just the inner electrons). If a valence electron was in a

state, this reduces the effective nuclear charge even further, to the point where that orbital may be unbound. This makes it more favourable for the valence electrons to all be in s orbitals, even if there are more valence electrons than can fit in a single s orbital. In simulations I’ve seen as many as 3 consecutive s orbitals occupied, with the largest being extremely spread out and low energy. These elements are probably like much more extreme versions of the alkali metals, with even lower ionization energies, and softer less dense metallic forms. I’ve been calling them “hyperalkali metals” for this reason.

state, this reduces the effective nuclear charge even further, to the point where that orbital may be unbound. This makes it more favourable for the valence electrons to all be in s orbitals, even if there are more valence electrons than can fit in a single s orbital. In simulations I’ve seen as many as 3 consecutive s orbitals occupied, with the largest being extremely spread out and low energy. These elements are probably like much more extreme versions of the alkali metals, with even lower ionization energies, and softer less dense metallic forms. I’ve been calling them “hyperalkali metals” for this reason.

- Hydrogen’s only excited states are 2s, 3s, 4s, etc.. No

- The ordering of the orbitals in energy changes significantly with changing atomic number

(and somewhat with changing mass number

(and somewhat with changing mass number  too). As

too). As  increases, the high-

increases, the high- orbitals decrease in energy (that is, their negative energies become larger) faster than the low-

orbitals decrease in energy (that is, their negative energies become larger) faster than the low- orbitals, and the energies often cross over. It’s not until element 21 that my Hartree-Fock simulations have shown any d orbitals being occupied at all (for the elements with

orbitals, and the energies often cross over. It’s not until element 21 that my Hartree-Fock simulations have shown any d orbitals being occupied at all (for the elements with  ), but just a few elements later the 1d orbital is lower in energy than the 2s, and as

), but just a few elements later the 1d orbital is lower in energy than the 2s, and as  increases, the 1d orbital approaches the 1s in energy. This leads to many cases where, as

increases, the 1d orbital approaches the 1s in energy. This leads to many cases where, as  increases, previously full sub-shells become empty or partially empty again, as other sub-shells with higher angular momentum surpass them. The periodic table, far from being periodic, becomes a total mess.

increases, previously full sub-shells become empty or partially empty again, as other sub-shells with higher angular momentum surpass them. The periodic table, far from being periodic, becomes a total mess.

The Angular Momentum Operator

The momentum operator in quantum mechanics is ![]() , meaning if a state

, meaning if a state ![]() satisfies

satisfies ![]() , it has a definite momentum

, it has a definite momentum ![]() , and

, and ![]() is the expected momentum of the state

is the expected momentum of the state ![]() (for

(for ![]() ).

).

Since the angular momentum ![]() 3In 3D the cross product is usually used, but the cross product does not generalize beyond 3D. The wedge product is more general. See Magnetism. in classical mechanics, the translation of this into quantum mechanics is the angular momentum operator

3In 3D the cross product is usually used, but the cross product does not generalize beyond 3D. The wedge product is more general. See Magnetism. in classical mechanics, the translation of this into quantum mechanics is the angular momentum operator ![]() . (In general

. (In general ![]() , so the quantum translation would be ambiguous, but they’re only different when

, so the quantum translation would be ambiguous, but they’re only different when ![]() , so this does not matter for the wedge product, which is antisymmetric. There’s another caveat that the particles’ spin contributes to the angular momentum too, and

, so this does not matter for the wedge product, which is antisymmetric. There’s another caveat that the particles’ spin contributes to the angular momentum too, and ![]() is just the orbital angular momentum.)

is just the orbital angular momentum.)

Another way to view the angular momentum operator is based on infinitesimal rotations. Let ![]() be the state

be the state ![]() rotated by an angle

rotated by an angle ![]() in the x-y plane. Then

in the x-y plane. Then

![]()

This establishes that the angular momentum operator commutes with the hamiltonian, ![]() , so

, so ![]() has the same energy as

has the same energy as ![]() .

.

The components of the angular momentum operator do not all commute with each other.

![]()

(returning to units where ![]() ). This means that, apart from the states with 0 angular momentum, there are no states with definite values of all angular momentum components simultaneously. This is another incarnation of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. We can however take the (scalar) square of

). This means that, apart from the states with 0 angular momentum, there are no states with definite values of all angular momentum components simultaneously. This is another incarnation of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. We can however take the (scalar) square of ![]() to measure the magnitude of the angular momentum, which gives

to measure the magnitude of the angular momentum, which gives

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[L^2 = r^2 \left(\nabla^2 - \frac{\partial^2}{\partial r^2}\right).\]](https://blog.4denthusiast.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9275951a7da5e50d284934189ec2c69c_l3.png)

This comes out with the opposite sign to usual because ![]() , but that’s merely a notational difference.

, but that’s merely a notational difference.

The relation of the angular momentum operator to the separation of variables discussed in the previous section now becomes clear. If ![]() is a separable wavefunction, then

is a separable wavefunction, then ![]() , and conversely, if a wavefunction has a definite value of

, and conversely, if a wavefunction has a definite value of ![]() , it is separable into a radial and an angular part.

, it is separable into a radial and an angular part.

![]() commutes with

commutes with ![]() , so it is also possible to find states with definite values of

, so it is also possible to find states with definite values of ![]() and, in 3D, a single component of

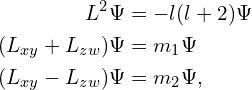

and, in 3D, a single component of ![]() , or in 4D, 2 perpendicular components, so in 3D,

, or in 4D, 2 perpendicular components, so in 3D,

and in 4D,

giving the last (in 3D) or last 2 (in 4D) quantum number(s) that define the orbital. ![]() is known as the magnetic quantum number, and it defines the particular orientation of the orbital within the sub-shell.

is known as the magnetic quantum number, and it defines the particular orientation of the orbital within the sub-shell.

The orbitals with definite magnetic quantum number(s) are not the same as the ![]() ,

, ![]() , etc. orbitals mentioned earlier, but this is merely a matter of picking a different basis. The

, etc. orbitals mentioned earlier, but this is merely a matter of picking a different basis. The ![]() orbitals for example are a complex linear combination of the

orbitals for example are a complex linear combination of the ![]() and

and ![]() orbitals, and the

orbitals, and the ![]() orbital is a combination of the

orbital is a combination of the ![]() and

and ![]() orbitals.

orbitals.

The angular momentum operators give another way of counting the orbitals in each sub-shell. This very standard argument can probably be found in most introductory quantum mechanics texts, so I will only briefly describe it here so that I can show how it works differently in 4D.

Applying one component of the angular momentum operator to a state can change that state’s value of the other components of ![]() . It is thereby possible to generate, from a single state of definite

. It is thereby possible to generate, from a single state of definite ![]() , all of the other

, all of the other ![]() states in the same sub-shell. The end result of this calculation, in 3D, is that

states in the same sub-shell. The end result of this calculation, in 3D, is that ![]() ranges from

ranges from ![]() to

to ![]() , giving

, giving ![]() possible states, as was already calculated by the polynomial method.

possible states, as was already calculated by the polynomial method.

The way that one operator changes another’s values is described by the commutator between the operators, ![]() , and if some non-empty set of operators is closed under linear combinations and commutators, it forms an algebraic structure known as a Lie algebra. The Lie algebra formed by the angular momentum operators in

, and if some non-empty set of operators is closed under linear combinations and commutators, it forms an algebraic structure known as a Lie algebra. The Lie algebra formed by the angular momentum operators in ![]() dimensions is

dimensions is ![]() , and it is from the structure of

, and it is from the structure of ![]() that the possible angular momentum states in 3 dimensions, with

that the possible angular momentum states in 3 dimensions, with ![]() for

for ![]() and

and ![]() , follow. (Actually there are additional options with

, follow. (Actually there are additional options with ![]() corresponding to spin states, but these do not give valid orbitals. The difference technically is that it must be a representation of the Lie group

corresponding to spin states, but these do not give valid orbitals. The difference technically is that it must be a representation of the Lie group ![]() not just the Lie algebra

not just the Lie algebra ![]() )

)

The Lie algebra ![]() happens to be isomorphic to

happens to be isomorphic to ![]() . More explicitly, the operators

. More explicitly, the operators ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() in 4D satisfy the same commutation relations as

in 4D satisfy the same commutation relations as ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() do in 3D, as do

do in 3D, as do ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , and the two sets of operators commute with each other. Following the same logic as the

, and the two sets of operators commute with each other. Following the same logic as the ![]() case for each set of operators separately therefore gives quantum numbers

case for each set of operators separately therefore gives quantum numbers ![]() , with

, with ![]() and

and ![]() . In this case though, the restriction required for something to be not merely a valid spin state but a valid orbital too is different, and

. In this case though, the restriction required for something to be not merely a valid spin state but a valid orbital too is different, and ![]() but they can still be half-integers. This gives a square of possible values of

but they can still be half-integers. This gives a square of possible values of ![]() , each ranging from

, each ranging from ![]() to

to ![]() . The magnetic quantum numbers may take half-integer values but they must differ from

. The magnetic quantum numbers may take half-integer values but they must differ from ![]() by an integer, so there are again

by an integer, so there are again ![]() possible values in total.

possible values in total.

Although I don’t expect to be going into relativistic 4D quantum chemistry, I may as well note the way that spin-orbital splitting works in 4D. In 3D, the ![]() spin of the electron combines with the integer angular momentum

spin of the electron combines with the integer angular momentum ![]() of the orbital to give a total angular momentum of either

of the orbital to give a total angular momentum of either ![]() or

or ![]() , with

, with ![]() of the higher spin orbitals and

of the higher spin orbitals and ![]() of the lower spin, and these orbitals have slightly different energies. In 4D, the electron’s spin is chiral, being

of the lower spin, and these orbitals have slightly different energies. In 4D, the electron’s spin is chiral, being ![]() in one of the

in one of the ![]() components and

components and ![]() in the other, therefore the sub-shells of angular momentum

in the other, therefore the sub-shells of angular momentum ![]() split into sub-shells of angular momentum

split into sub-shells of angular momentum ![]() and

and ![]() , with

, with ![]() orbitals of the higher spin, and

orbitals of the higher spin, and ![]() of the lower. Because the S force prevents the electrons from closely approaching the nucleus in 4D (with the exception of hydrogen 1), the maximum speed and energy of the electrons increases more slowly as

of the lower. Because the S force prevents the electrons from closely approaching the nucleus in 4D (with the exception of hydrogen 1), the maximum speed and energy of the electrons increases more slowly as ![]() increases than in 3D, therefore relativistic effects will be not so important even for heavy elements, probably remaining merely a small splitting observable in spectral lines.

increases than in 3D, therefore relativistic effects will be not so important even for heavy elements, probably remaining merely a small splitting observable in spectral lines.

- 1in principle it takes complex values, but all of the actual solutions can be made real just by a re-scaling

- 2I’m not quite sure yet this is the right criterion. I realised there was an error in my original reasoning only after publishing the post, and I’ve not yet worked out the correct answer, but this should be approximately right)

- 3In 3D the cross product is usually used, but the cross product does not generalize beyond 3D. The wedge product is more general. See Magnetism.

Leave a Reply