The basic principle from which almost1The main exception is relativistic phenomena, which are not as relevant in 4D, and there’s also some information needed about interpretation which isn’t included in the equation itself. all of chemistry can in principle be derived is the Schrödinger Equation. The study of real chemistry tends to be more focused on experimentation rather than simulation, and for good reason. Actually calculating things all the way from this basic level (“ab initio”) is often computationally impractical, and requires approximations that obviously aren’t present if you just use actual atoms, but since I don’t have any actual 4D atoms, here there is no alternative. That’s not to say this sort of simulation isn’t done in some cases for real life chemistry too, it’s called computational chemistry. It’s a lot quicker to make a computer model of a drug candidate than to actually synthesise it for example (assuming you already have the software to do this).

There are of course a lot of introductions to this topic elsewhere online, but I figure people would find it easier to get this information here if they’re just using it to understand my other posts. Also, there’s an awful lot to cover and I’ll try to stick to just the relevant bits. Except where otherwise noted, all the chemistry in this post will be real 3D chemistry.

The Time-Dependent Schrödinger Equation

In classical mechanics, the state of a particle (with no internal structure) at a certain moment in time is represented by two vectors, its position and velocity. In quantum mechanics, particles don’t generally have single well-defined values of these variables, and the state must instead be represented by a wavefunction.

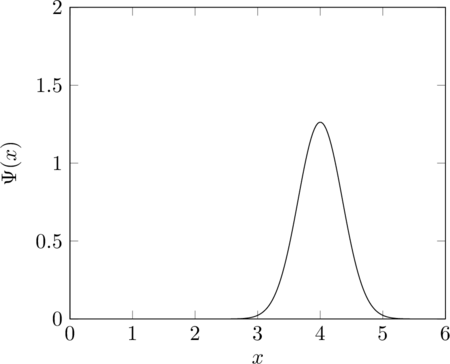

The graph shows an example of a wavefunction for a single 1D particle which is located somewhere around the point 4. ![]() is a function from the position of the particle (in the 1D case just a single number, the 3D case is harder to show on a graph) to a complex number. The square of the magnitude of the wavefunction at a point is the probability density for the particle to be found to be there if it is observed. The momentum of a particle is also encoded in its wavefunction, though less directly (at least in this representation). Although it is only the magnitude of the wavefunction that determines the particle’s position, its phase (and in particular the variation of phase with position) also contributes to the momentum. If the wavefunction includes some portion of multiple different states, the system is said to be in a superposition of these states. In the graph above, the particle is in a superposition of being at position 4, being at 3.5, and so on. It can also be described as being in a superposition of different momentum states.

is a function from the position of the particle (in the 1D case just a single number, the 3D case is harder to show on a graph) to a complex number. The square of the magnitude of the wavefunction at a point is the probability density for the particle to be found to be there if it is observed. The momentum of a particle is also encoded in its wavefunction, though less directly (at least in this representation). Although it is only the magnitude of the wavefunction that determines the particle’s position, its phase (and in particular the variation of phase with position) also contributes to the momentum. If the wavefunction includes some portion of multiple different states, the system is said to be in a superposition of these states. In the graph above, the particle is in a superposition of being at position 4, being at 3.5, and so on. It can also be described as being in a superposition of different momentum states.

The time evolution of the wavefunction is described by the Schrödinger equation.

![]() is just a constant which I will mostly be ignoring (it is possible to change the units so that it is 1, and I will be doing so for the rest of this post) but it is worth noting that the fact that

is just a constant which I will mostly be ignoring (it is possible to change the units so that it is 1, and I will be doing so for the rest of this post) but it is worth noting that the fact that ![]() ‘s value is so small by ordinary human standards (at approximately

‘s value is so small by ordinary human standards (at approximately ![]() ) is an important part of the reason quantum phenomena are not visible at these scales.

) is an important part of the reason quantum phenomena are not visible at these scales. ![]() is the potential. It describes how much potential energy the particle would have at a given position and time. If the particle is charged, it might include a term for the electric field, for example.

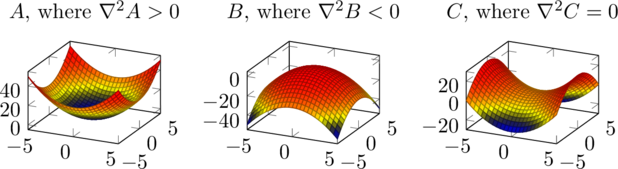

is the potential. It describes how much potential energy the particle would have at a given position and time. If the particle is charged, it might include a term for the electric field, for example. ![]() is the Laplacian, equal to the sum of the second derivatives along each axis (of the axes that make up the vector

is the Laplacian, equal to the sum of the second derivatives along each axis (of the axes that make up the vector ![]() ), or more informally the total curvature of the function.

), or more informally the total curvature of the function.

The sort of calculations I’ll be doing are mostly not actually concerned with dynamics though, only the energies of static systems, so rather than go into more detail on how this version of the Schrödinger Equation works, let’s skip straight on to

The Time-Independent Schrödinger Equation

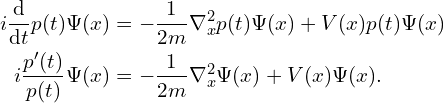

In quantum mechanics, a state has a definite energy if and only if it does not change over time. The overall phase can change, so long as ![]() for some complex number of unit magnitude

for some complex number of unit magnitude ![]() . The overall phase is not observable, so this still counts as staying the same. Plugging this in to the Schrödinger Equation, and assuming the potential does not depend on time, we get

. The overall phase is not observable, so this still counts as staying the same. Plugging this in to the Schrödinger Equation, and assuming the potential does not depend on time, we get

Since both ![]() and the right hand side are constant in time,

and the right hand side are constant in time, ![]() is constant too. It turns out this is the energy, so let’s call it

is constant too. It turns out this is the energy, so let’s call it ![]() , then the new time-independent form of the Schrödinger Equation for states of energy

, then the new time-independent form of the Schrödinger Equation for states of energy ![]() becomes

becomes

For a given potential ![]() , there are generally only certain values of

, there are generally only certain values of ![]() which can satisfy this equation for any

which can satisfy this equation for any ![]() which has total probability 1. These values of

which has total probability 1. These values of ![]() are called eigenstates, because they are eigenvectors of

are called eigenstates, because they are eigenvectors of ![]() . For any

. For any ![]() there is a trivial solution

there is a trivial solution ![]() , and there are often solutions where

, and there are often solutions where ![]() grows exponentially with

grows exponentially with ![]() , but neither of these can be normalised therefore they do not count as valid solutions. There are also sometimes solutions like

, but neither of these can be normalised therefore they do not count as valid solutions. There are also sometimes solutions like ![]() for

for ![]() and

and ![]() (for any

(for any ![]() which tends to a constant sufficiently fast as

which tends to a constant sufficiently fast as ![]() tends to infinity, there will be solutions which are minor variations on this, although they generally don’t have such neat formulas). These are not normalisable either, but they are usually counted anyway because they can be made normalisable if

tends to infinity, there will be solutions which are minor variations on this, although they generally don’t have such neat formulas). These are not normalisable either, but they are usually counted anyway because they can be made normalisable if ![]() is allowed to vary slightly, and they correspond to situations which are physically realistic where the particle is travelling freely, not bound by the potential. Thankfully these solutions and the complexities associated with their lack of normalization don’t come up so much in chemistry.

is allowed to vary slightly, and they correspond to situations which are physically realistic where the particle is travelling freely, not bound by the potential. Thankfully these solutions and the complexities associated with their lack of normalization don’t come up so much in chemistry.

The remaining common class of solutions is bound states, where ![]() and

and ![]() can both only take certain discrete values. Most systems generally have a tendency to move to states of low energy. Technically energy is conserved so there must be other parts of the world that increase in energy to compensate, but this intuition will do fine here. The state in which a chemical system can most often be found is therefore the state of lowest energy, known as the ground state, so to calculate the properties of an atom or small molecule2The larger a molecule is, the more states it has other than the ground state, and the more likely it is some of them will only differ very slightly in energy from the ground state, so it is more likely the molecule will not be found in the ground state and it becomes more necessary to consider a range of states., the most important step is to find the ground state.

can both only take certain discrete values. Most systems generally have a tendency to move to states of low energy. Technically energy is conserved so there must be other parts of the world that increase in energy to compensate, but this intuition will do fine here. The state in which a chemical system can most often be found is therefore the state of lowest energy, known as the ground state, so to calculate the properties of an atom or small molecule2The larger a molecule is, the more states it has other than the ground state, and the more likely it is some of them will only differ very slightly in energy from the ground state, so it is more likely the molecule will not be found in the ground state and it becomes more necessary to consider a range of states., the most important step is to find the ground state.

Heisenburg’s Uncertainty Principle

In a system with an electron and a nucleus, there are small regions of space with very low (large and negative) potential energy, where the electron is very close to the nucleus and the electrostatic interaction is strong. If we neglect the kinetic energy term, the Schrödinger Equation becomes simply ![]() , so the lower the potential energy, the lower the total energy, and the ground state would simply have the electron as close to the nucleus as possible. The kinetic energy term

, so the lower the potential energy, the lower the total energy, and the ground state would simply have the electron as close to the nucleus as possible. The kinetic energy term ![]() prevents this from happening (in 3D at least. See Scale for why this doesn’t work the same way in 4D). Since the wavefunction represents both the position and momentum of the particle, it is not possible to set the position arbitrarily without it having an influence on the momentum too. The momentum is proportional to the gradient of the wavefunction, which is why the kinetic energy depends on this gradient. The more concentrated the position is in one region of space, the more the momentum must be spread out over a large region of momentum space, and the larger the momentum, the larger the kinetic energy.

prevents this from happening (in 3D at least. See Scale for why this doesn’t work the same way in 4D). Since the wavefunction represents both the position and momentum of the particle, it is not possible to set the position arbitrarily without it having an influence on the momentum too. The momentum is proportional to the gradient of the wavefunction, which is why the kinetic energy depends on this gradient. The more concentrated the position is in one region of space, the more the momentum must be spread out over a large region of momentum space, and the larger the momentum, the larger the kinetic energy.

This restriction can be made precise in the form of the Heisenburg Uncertainty Principle, ![]() . The angle brackets denote averages. If the value of the position

. The angle brackets denote averages. If the value of the position ![]() does not vary much from its average

does not vary much from its average ![]() , then the momentum

, then the momentum ![]() must have a high variance to compensate.3The reason I am using capital

must have a high variance to compensate.3The reason I am using capital ![]() and

and ![]() here for the position and momentum, unlike elsewhere where I’ve been using

here for the position and momentum, unlike elsewhere where I’ve been using ![]() , is that these averages are technically defined for operators, which are beyond the scope of this quick introduction.

, is that these averages are technically defined for operators, which are beyond the scope of this quick introduction.

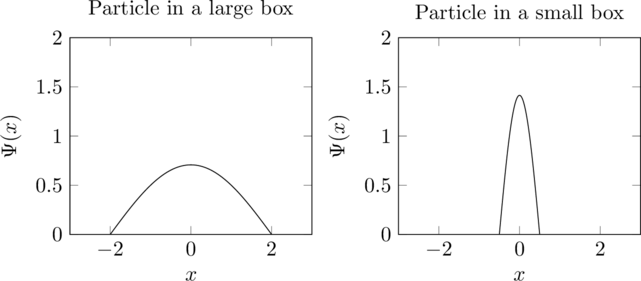

As an example, let’s consider a system where a particle can travel in 1D, but only between the bounds ![]() to

to ![]() . Inside of this range, the potential is

. Inside of this range, the potential is ![]() . Outside, it is infinite. The ground state of this system has wavefunction

. Outside, it is infinite. The ground state of this system has wavefunction ![]() inside of the bounds and

inside of the bounds and ![]() outside. The kinetic energy term is

outside. The kinetic energy term is ![]() , therefore the energy increases proportionally to

, therefore the energy increases proportionally to ![]() as the size of the box decreases.

as the size of the box decreases.

In these graphs, the second wavefunction is clearly more curved because it has to fit into a smaller space, which makes the value of the Laplacian, and therefore the kinetic energy, larger.

Since the kinetic energy term tends to make the ground state more spread out and the potential energy is low only in certain regions, the actual ground state is a compromise between these two tendencies, varying smoothly but with peaks where the potential is lowest.

One of the only actual chemical systems for which the Schrödinger Equation can be solved exactly is a system in which there is just one electron and one nucleus. If we treat the nucleus as fixed (or equivalently, as having infinite mass), the equation for this case becomes

where ![]() is the permittivity of the vacuum, a constant that determines the overall strength of electric interactions,

is the permittivity of the vacuum, a constant that determines the overall strength of electric interactions, ![]() is the atomic number,

is the atomic number, ![]() is the charge of an electron and

is the charge of an electron and ![]() is the distance between the electron and the nucleus. The ground state solution is

is the distance between the electron and the nucleus. The ground state solution is

or, setting as many constants as possible to ![]() ,

,

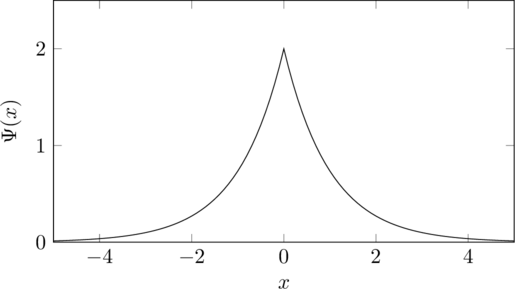

which has an energy of ![]() and has this shape but as a 3D sphere.

and has this shape but as a 3D sphere.

Multiple Particles

So far, I have been discussing systems with only a single particle, because there is a bit of a conceptual complexity you must understand about quantum mechanics before being able to deal with systems of multiple particles. Different particles in QM do not have separate states like they do in classical mechanics. Instead, there is a single wavefunction governing all of the particles. If the positions of the particles are ![]() , the wavefunction is a function of all of these at once,

, the wavefunction is a function of all of these at once, ![]() . The (time-independent) Schrödinger Equation then becomes

. The (time-independent) Schrödinger Equation then becomes

The potential is also a function of all of the particles at once, which allows it to include the interactions between them. If particles ![]() and

and ![]() are electrons, for example, there would be a term

are electrons, for example, there would be a term ![]() for their electric repulsion.

for their electric repulsion.

It is sometimes possible to express these many-particle wave functions as products of parts depending on only some of the variables. If the particles can be separated into two groups which do not interact, i.e. ![]() , and

, and ![]() and

and ![]() are states of energy

are states of energy ![]() and

and ![]() under these two partial potentials, then

under these two partial potentials, then ![]() is a solution to the Schrödinger equation under the combined potential

is a solution to the Schrödinger equation under the combined potential ![]() with energy

with energy ![]() . This is why non-interacting systems can be treated as separate even though they are all in a sense part of a single universal wavefunction.

. This is why non-interacting systems can be treated as separate even though they are all in a sense part of a single universal wavefunction.

Even when particles do interact, a separable wavefunction can still sometimes be a useful approximation.

Pauli Exclusion Principle

There is an additional restriction on the multi-particle wavefunction in the case that some of the particles are identical. If particles ![]() and

and ![]() are identical and they are fermions (a class of particles that includes electrons), the wavefunction must undergo a change in sign but otherwise be unchanged if the positions of the two particles are swapped, i.e. it must satisfy the equation

are identical and they are fermions (a class of particles that includes electrons), the wavefunction must undergo a change in sign but otherwise be unchanged if the positions of the two particles are swapped, i.e. it must satisfy the equation ![]() . (If they are bosons, the other sort of particle, the same equation applies but without the sign change, but that is less relevant because electrons are by far the most important particles in chemistry.)

. (If they are bosons, the other sort of particle, the same equation applies but without the sign change, but that is less relevant because electrons are by far the most important particles in chemistry.)

This adds an extra complication to the behaviour of non-interacting particles as described in the previous section. If ![]() and

and ![]() are two possible single-electron wavefunctions in a certain system, then even neglecting the interaction between them,

are two possible single-electron wavefunctions in a certain system, then even neglecting the interaction between them, ![]() is not a good two-electron wavefunction because it isn’t antisymmetric. This can be fixed by instead taking

is not a good two-electron wavefunction because it isn’t antisymmetric. This can be fixed by instead taking ![]() (times some normalising constant), which has the same property as

(times some normalising constant), which has the same property as ![]() that if the component wavefunctions satisfy the Schrödinger Equation, so does the composite wavefunction, but if

that if the component wavefunctions satisfy the Schrödinger Equation, so does the composite wavefunction, but if ![]() , this doesn’t work because

, this doesn’t work because ![]() , so there is no state where both electrons are in this same state. In a many-electron system, this restriction means that the electrons can’t all just go into the lowest-energy state. Instead, (to the extent they can be described as having well-defined individual states at all), they must each have a different state, with one electron in the lowest energy state, one in the second lowest and so on. Because the possible states and energies are discrete, the second-lowest energy can be significantly higher than the lowest. This principle, the Pauli Exclusion Principle, is responsible for a lot of the variation in chemistry by preventing degenerate behaviour.

, so there is no state where both electrons are in this same state. In a many-electron system, this restriction means that the electrons can’t all just go into the lowest-energy state. Instead, (to the extent they can be described as having well-defined individual states at all), they must each have a different state, with one electron in the lowest energy state, one in the second lowest and so on. Because the possible states and energies are discrete, the second-lowest energy can be significantly higher than the lowest. This principle, the Pauli Exclusion Principle, is responsible for a lot of the variation in chemistry by preventing degenerate behaviour.

Although each electron must have a different state, this does not quite mean they all have to have different spatial locations, because there is one more part of an electron’s state which I have been neglecting so far, its spin. The spin can take one of two possible values, normally labelled up and down, or any superposition of these. The superpositions don’t count as separate states for the purpose of the exclusion principle, so effectively there can be two electrons per orbital (the orbitals being roughly the one-electron wavefunctions depending only on position). The spin states have different magnetic moments and behave a little differently at relativistic speeds, but mostly they are similar and the important thing is simply that there are two of them.

Bonding

To illustrate how all this leads to familiar chemical behaviour, I will give a brief discussion of why bonding occurs in the simplest possible system with multiple atoms. More complicated systems will have to wait for more tools explained in later posts.

The hydrogen moleclar ion is a system of two hydrogen nuclei and one electron. For each of the nuclei, there is a 1s orbital ![]() given by

given by ![]() and

and ![]() (a 1s orbital is just an orbital of this sort of shape). If the nuclei are very far apart, the electron can only interact with one nucleus at a time, so each of these is a valid wavefunction with energy

(a 1s orbital is just an orbital of this sort of shape). If the nuclei are very far apart, the electron can only interact with one nucleus at a time, so each of these is a valid wavefunction with energy ![]() . If the nuclei are close together, these are no longer energy eigenstates, but we can approximate the wavefunction as a linear combination (superposition) of them. Because of the symmetry of the system, the wavefunction should also be symmetric, so it’s either

. If the nuclei are close together, these are no longer energy eigenstates, but we can approximate the wavefunction as a linear combination (superposition) of them. Because of the symmetry of the system, the wavefunction should also be symmetric, so it’s either ![]() or

or ![]() . To put it briefly,

. To put it briefly, ![]() has lower kinetic energy because the gradients of the orbitals on each atom cancel each other out in the area of space between the nuclei, and the potential energy is also lowered because the orbitals constructively interfere in the region between the nuclei where the potential is lowered.

has lower kinetic energy because the gradients of the orbitals on each atom cancel each other out in the area of space between the nuclei, and the potential energy is also lowered because the orbitals constructively interfere in the region between the nuclei where the potential is lowered. ![]() has higher energy because the opposite of each of these effects occurs.

has higher energy because the opposite of each of these effects occurs.

Even if a given wavefunction is not actually an energy eigenstate, it is possible to calculate its average energy anyway. This average is always at least the ground state energy, because a general state is a mixture of eigenstates and all of the other eigenstates have energies at least the ground state energy. The closer the approximation is to the ground state, the lower its energy and the better this approximation, but so long as it is lower than the exact unbonded energy (which we know in this case because there’s only one electron), that’s enough to prove that bringing the nuclei close lowers the energy therefore bonding is occurring.

The average energy is defined as

This requires that ![]() is correctly normalised. It is also written

is correctly normalised. It is also written ![]() as shorthand, where

as shorthand, where ![]() .

.

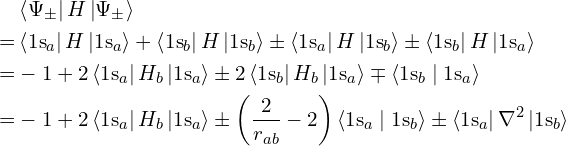

Let’s apply this to the two wavefunctions ![]() and

and ![]() (and divide by

(and divide by ![]() to compensate for the fact that they aren’t normalized). Since

to compensate for the fact that they aren’t normalized). Since ![]() is an eigenfunction for the portion of

is an eigenfunction for the portion of ![]() excluding the interaction with nucleus

excluding the interaction with nucleus ![]() , we can express

, we can express ![]() as

as ![]() where

where ![]() , and vice-versa.

, and vice-versa.

The term ![]() evaluates to

evaluates to ![]() which for large distances

which for large distances ![]() between the nuclei is smaller than the other terms and can be ignored.

between the nuclei is smaller than the other terms and can be ignored.

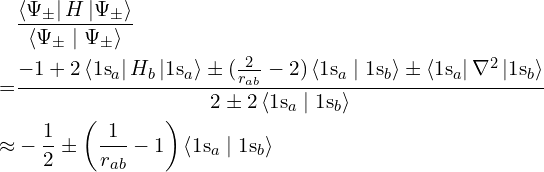

with the approximation being valid for large distances between the nuclei. Since ![]() is positive, this means that

is positive, this means that ![]() has lower energy than the unbonded atoms for sufficiently large separation between the nuclei. This energy gets lower until the nuclei become so close that their repulsion, with energy

has lower energy than the unbonded atoms for sufficiently large separation between the nuclei. This energy gets lower until the nuclei become so close that their repulsion, with energy ![]() , overcomes the lowering of the electron’s energy, which tends to

, overcomes the lowering of the electron’s energy, which tends to ![]() as

as ![]() tends to 0. There is therefore some intermediate distance at which the overall lowest energy is reached, and the molecule is stable there.

tends to 0. There is therefore some intermediate distance at which the overall lowest energy is reached, and the molecule is stable there.

For more complicated atoms, sometimes the interaction is attractive and sometimes it’s repulsive, depending on whether the electrons are able to end up in bonding orbitals of lowered energy like ![]() or whether there are too many that are forced to end up in repulsive anti-bonding orbitals like

or whether there are too many that are forced to end up in repulsive anti-bonding orbitals like ![]() .

.

- 1The main exception is relativistic phenomena, which are not as relevant in 4D, and there’s also some information needed about interpretation which isn’t included in the equation itself.

- 2The larger a molecule is, the more states it has other than the ground state, and the more likely it is some of them will only differ very slightly in energy from the ground state, so it is more likely the molecule will not be found in the ground state and it becomes more necessary to consider a range of states.

- 3The reason I am using capital

and

and  here for the position and momentum, unlike elsewhere where I’ve been using

here for the position and momentum, unlike elsewhere where I’ve been using  , is that these averages are technically defined for operators, which are beyond the scope of this quick introduction.

, is that these averages are technically defined for operators, which are beyond the scope of this quick introduction.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ E\Psi = -\frac 1 {2m} \nabla^2 \Psi - \frac 1 {4 \pi \varepsilon_0} \frac {Z e^2} r \Psi \]](https://blog.4denthusiast.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-389bb8255601bc35cb277cd432c4ad00_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\Psi = \frac 1 {8 \pi^2} \left(\frac {Zme^2}{\varepsilon_0}\right)^{\frac 3 2} e^\frac{-Zrme^2}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\]](https://blog.4denthusiast.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-5d3fdf0f2c64507bfca25a6810557c6c_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ E\Psi(x_0,\dots) = -\sum_i \frac 1 {2m_i} \nabla^2_{x_i} \Psi(x_0,\dots) + V(x_0,\dots) \Psi(x_0,\dots). \]](https://blog.4denthusiast.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f9efcf391da065b350798d8298441b1a_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \langle E \rangle = \int_x \Psi(x)^\ast \left(-\frac 1 {2m} \nabla^2_x \Psi(x) + V(x) \Psi(x)\right) \mathrm dx \]](https://blog.4denthusiast.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-80c8b82b255214c3ca8fe4ba72faedf4_l3.png)

Leave a Reply